Some of you who know me might know that I play the saxophone. While I'm definitely not a professional, I've done a few performances here and there.

Here are some throwbacks!

Man... those hippie days when I had long curly hair and tried to compensate for the cool factor with a good ol' bucket hat. Not the best look.

And... I've had my fair share of super embarrassing moments performing on this instrument.

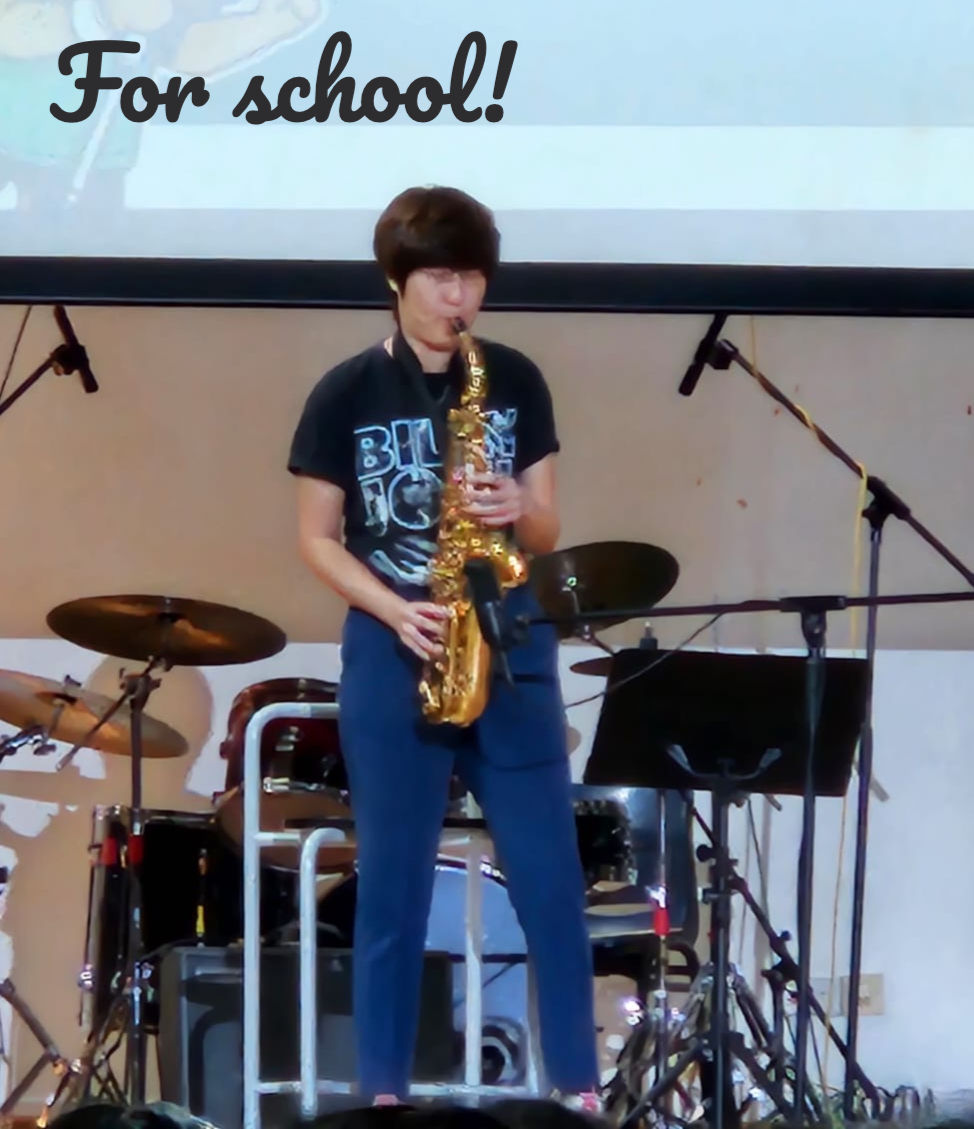

Take for example, on the left, and the reason why you should never perform in front of a bunch of mischievous, not-so-mature 18 year olds – you might be made into a meme sent around group chats as a Christmas greeting. Thanks a lot, 23S03N.

As a self-taught saxophonist, I must say learning experiences come pretty painfully. The very first time I performed, I didn't know that the G# was a "sticky" key, i.e. if you don't dry the pads of your saxophone properly and let humidity build up, the G# pad could get stuck, not opening even if you press it. That led to a pretty horrifying off-key G note on stage, in front of everyone, mic-ed up and LOUD. Safe to say the audience was pretty blown away. Yes, unfortunately, playing the saxophone ain't always saxxy.

Those awkward, cringeworthy moments were behind me.... or so I thought.

Storytime! This year, a few colleagues (qtpies featured below!) and I performed the classic Lean on Me by Mr. Bill Withers for our students' farewell assembly. I'll be honest with you, I was quite confident going into the performance, considering that I sounded pretty consistent on my sax solo throughout the rehearsals.

Thinking that everything will be ok, I tuned my saxophone, then left it on stage for a good 1 to 2 hours before our performance. (gasp....this is where shit hit the fan)

The stage was cold, which meant that my saxophone got cold too. The saxophone is mostly made of metal (brass) i.e. a good conductor of heat, therefore turning cold pretty fast.

When I got on stage, I picked up my saxophone and it was cold to touch, but silly me didn't think much of it. Lo and behold, when I played the very first note, a high C# coming into my solo, I was flat. Completely flat. Well, not flat by a whole semitone, but by a considerable number of cents, probably more than 25 cents (1 semitone = 50cents). I would assume that the sound was flat enough to be noticed by even an untrained ear.

What was I to do? I was a little startled, but I just trudged along, finishing the solo. As I continued into the second half of my solo, I realised that my pitch stabilised again – I was in tune!

This experience seriously confuzzled me. Yes, a mix of confusement and puzzlesion. I looked it up and I found two possible hypotheses:

The saxophone contracted in the cold, thus becoming shorter/smaller.

The smaller an instrument, the higher its pitch; and conversely, the larger an instrument, the lower its pitch.

Take for example, the bass saxophone is the largest/longest, producing the lowest range of sounds while the soprano saxophone is the smallest/shortest, producing the highest range of sounds. This is the same for any other set of instruments – say violin (small and high-pitched) vs. cello (large and low-pitched).

This is because the shorter the instrument, the faster sound travels through it. Since frequency = 1/time period, a shorter time period would mean a sound wave of higher frequency, or pitch.

Try blowing through a straw to produce a sound. Then gradually cut the straw shorter and shorter. You will notice a higher pitch each time you cut the straw!

However, this hypothesis obviously failed to explain my experience. If my saxophone contracted, shouldn't it now be shorter, resulting in a higher pitch (sharp) rather than a lower one (flat)? Furthermore, I don't think leaving my saxophone in the cold for 1 or 2 hours would have contracted it significantly.

So I thought of hypothesis 2:

The air blown through the saxophone became colder, decreasing the speed of sound.

Let's try to understand the fundamentals of how a sound is created – Sound waves are created when an object vibrates, causing nearby air molecules to vibrate as well. These vibrations pass from one molecule to the next, creating a wave that travels through the medium (in this case, air).

In warmer air, the increased kinetic energy of the molecules means they move faster and collide more frequently. This facilitates quicker transfer of the sound energy from one air molecule to the next. As a result, sound waves can propagate more rapidly through air. Essentially, the faster movement of the molecules helps transmit the sound energy more efficiently, allowing the sound to travel faster in hot air compared to cold air.

Therefore, the warmer the air, the faster sound travels, therefore increasing frequency/pitch (f = 1/t), sharpening the note. Conversely, the colder the air, the flatter the note.

That explains it! It felt like a huge moment of relief once I understood what happened on stage. It was like "oh, it was not my technique that killed the performance, it was just my stupidity."

There were two things that I could have done to avoid this problem in a cold room:

- Tune my saxophone to a higher pitch i.e. move my mouthpiece further onto the neck.

- Close all pads and blow warm air into the saxophone for a few mins before the solo. (Yes, just like a human voice, a cold saxophone needs some warming up. Give it some TLC before you start playing!)

Considering how hot and humid Singapore can be sometimes, if I were to play outdoors under scorching weather, I would do the opposite – tune my saxophone slightly flat.

All in all, while I was kind of bummed at first, I was actually glad things turned out the way it did. Because I wouldn't have known if I hadn't made this error.

Here's to making more mistakes, learning from them and becoming a better performer!

Comments